Two men asked him for a loan. He gave them both a generous sum on condition that he’d be repaid in a year’s time. A year later the debtors returned. One looked broke.

“Unfortunately, I do not have the money to repay you,” he began. “Honestly, it was so liberating to have some cash. I started spending. Soon the spending became addictive. Ultimately I could not sustain my lifestyle, and so here I am—one year later and broke again.”

“I do not forgive the loan,” replied the philanthropist.

The second debtor returned the entire sum he’d borrowed. “I started a small business,” he explained. “It was difficult, but things are finally starting to progress. Here’s your money—thanks for giving me the opportunity to get myself on my feet.”

“Please, keep the money. Let me be your business partner.”The priest leaves the Temple to meet themetzora on his terms

Tzaraat (commonly translated as “leprosy”) was a supra-natural bodily affliction. Our sages say that it was contracted from speaking lashon hara, gossip. The metzora (as the one who contracted tzaraat is called) would remain isolated outside the encampment until he was restored to health. The Torahtalks at length about the metzora’s healing process. A priest would travel to themetzora and dip cedar wood, scarlet thread and a hyssop plant into a mixture of bird’s blood and spring water, and sprinkle it on the metzora seven times. Seven days later, the metzora would shave his hair and immerse in a mikvah (ritual pool) to culminate his healing.

This is how the Torah describes the meeting between the metzora and the priest:

This shall be the law of the metzora on the day of his cleansing: he shall be brought to the priest. The priest shall go out of the camp; and the priest shall look, and see if the plague of tzaraat has been healed . . . (Leviticus 14:2)

The Torah’s instructions seem to be conflicting. Initially we read that “he [themetzora] shall be brought to the priest,” and then, in the next verse, “the priest shall go out of the camp.” Does the metzora go to meet the priest, or does the priest come to him?1

We can see an organic reconciliation between the conflicting instructions when we view the metzora through the lens of Kabbalah. Mystically, the metzora is the persona of an individual who doesn’t see the unifying thread of divinity running through his life. That’s why he’s insensitive to the social discord he creates through his gossip. When we gossip, we create an energetic rift—between my impulsive tongue and your sacred privacy, and ultimately, a schism between spiritual and practical existence. Maimonides goes so far as to say that one who speaks lashon hara will come to speak words of heresy against G‑d.

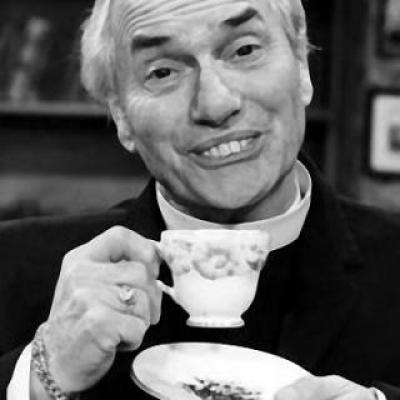

The priest’s life, on the other hand, is all about devotion to G‑d. His life is all about his divine service.

What the metzora needs is some face time with the priest.

With warmth and empathy, the priest leaves the Temple to meet the metzora on his terms, disenfranchised as he is from the Jewish nuclear heartbeat. This gesture alone brings an awareness of G‑d’s unity to the metzora. He’s touched, inspired; he’s on his way to spiritual wellness.His healing requires a fusion of the priest’s influence with his own work

But were he to remain a passive recipient of the priest’s influence, the inspiration would be fleeting—since it wouldn’t be his own. It would impact him so long as the priest was in his company, but without any proactive initiative, the metzora would have no tools to process his new awareness.

This shall be the law of the metzora on the day of his cleansing; he shall be brought to the priest.

When the metzora walks towards the priest, he begins to take ownership of his cleansing opportunity and make it his own. His healing requires a fusion of the priest’s influence with his own work, to integrate this awareness shift into his life.2

I find the swing from inspiration and proactivity to be a lifelong dance. For a stretch of time I devoted most of my day to the study of Torah and chassidic teachings, and I was surrounded by mentors who spoke the message of G‑d’s unity through their teachings and their conduct.

And then it was over. No more spoon-fed inspiration. Now came the true challenge of self-initiated growth—the challenge to integrate the gifts I’d gleaned. If I could generate that awareness now, then I’d make it my own. The priest had come to visit me on my terms; now could I take my own steps towards him.

I’m thinking of a story I’d heard about the Lubavitcher Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory. In a conversation with a certain rabbi from outside New York, the Rebbe inquired about a member of his community. Then the Rebbe told him the following: “I’d like you to encourage this congregant to grow a beard this year—but please do not let him know that this request is coming from me!”

The rabbi spoke to his friend about taking this step forward in Jewish observance, but he wasn’t successful in persuading him. Finally, in desperation, he divulged his secret. “The Lubavitcher Rebbe personally asked that you grow a beard.”

“In that case, I’ll do it!”

During his next audience with the Rebbe, the rabbi informed the Rebbe that his congregant had made the commitment.

“And did you tell him that this request was coming from me?” the Rebbe asked.

“Yes, I finally did tell him . . . ,” the rabbi was forced to concede. “But, Rebbe, what difference does it make—at least he’s doing it!”

“True,” the Rebbe responded, “but I wanted it to be his beard, not my beard.”

FOOTNOTES 1.

A pragmatic resolution of these two verses may be that the metzora should be brought to the very outer edge of the encampment’s border in preparation for the priest’s arrival. But yet, this resolution doesn’t suffice. Why would the Torah assume that the metzora had traveled beyond the border of the encampment and ventured further out?

2.Based on a talk by the Rebbe, recorded in Likkutei Sichot, vol. 7, pp. 100ff.